Trout Anatomy Part 2

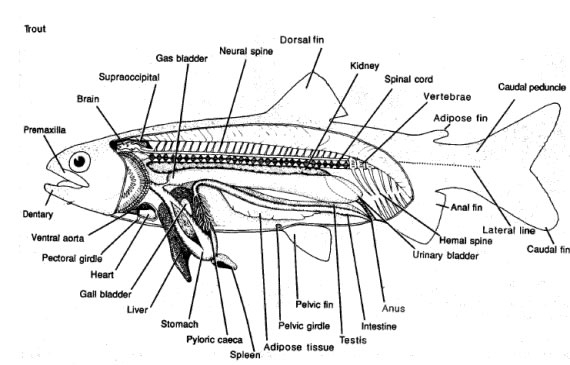

Last time I talked a little about the externals of a trout. Things like the caudal peduncle and the auxiliary pelvic appendage. I love showing people the auxiliary pelvic appendage. I have shown many trout anglers this interesting feature and they are shocked that they haven’t noticed it after handing many salmonids. This time around I want to talk about a few internal features that you might see in a trout and have wondered about over the years. There are a few specific internal organs that are of particular interest to the trout angler.

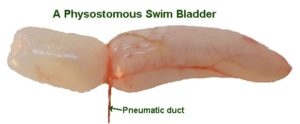

I am sure many of you have witnessed a distended air bladder. You know… the air bladder that has inflated on a lake trout after you have brought it to the surface from the depths. Have you ever observed a lake trout “burp” air as it is nearing the surface? I am going to introduce you to two words that you may have heard before. The words are physoclistous and physostomous.

These words describe two categories of fish. A basic understanding of these terms will help us obtain a better grasp on how an air bladder works. The air bladder is an amazing little “bag of gas” inside a trout that allows it to control buoyancy. Squeeze a trout too hard and you may hear a strange escape of air sound. That is the gas bladder emptying.

How many of you have caught a lingcod before? You will notice that when you land a lingcod from great depth that it will not have a distended air bladder. But, if you land a vermilion rockfish from the same depth it will have that air bladder sticking out of its mouth.

The lingcod is what we call a physostomous fish. That means that is has a connection from the air bladder to the mouth and can adjust the air bladder by either adding or removing air via the mouth. This will allow the lingcod to keep up with the aggressive pressure changes that will happen during a fight to the boat. The vermilion on the other hand is a physoclistous fish. This means that it does not have the connection from the air bladder to the mouth and is only able to adjust the air bladder through the much slower process of diffusion.

All trout are physostomes, but the duct that connects the gas bladder to the mouth is narrow and they cannot equalize as quickly as a lingcod. Thus, if you fight a trout to the boat in a quick fashion from depth the gas bladder will expand as the pressure decreases and the trout will have a hard time releasing any air from the bladder. If you are able to fight the trout to the boat from depth in a slower manner then the trout may be able to expel some of the expanding gas from the gas bladder through its mouth and keep the gas bladder from expanding too rapidly… thus the “burping” that many of you have witnessed from Mackinaw, which is a very deep living “trout”.

I have already covered the proper release methodologies for trout having a distended air bladder in another article so I will not repeat them here. The main thing to realize is that without proper release techniques a trout with a distended air bladder can easily die.

I hope this was of interest to those of you that are curious in all aspects of the trout. Next time I will cover something that I find very interesting… pyloric caecum!

Mark Knoch